- Home

- C. Robert Cargill

Queen of the Dark Things Page 5

Queen of the Dark Things Read online

Page 5

“Colby, I need my children.”

Colby flipped a cigarette into his mouth, flicking the lighter, and lighting his smoke in one fluid motion. “Those aren’t your kids, and you know it, witch.”

Beatriz tightened, her arms drawing close, her fingers becoming long and sharp. She hissed and the air around her chilled, frosting the water on her skin. Then she took another sloshing step forward. Colby took a long, slow drag on his cigarette, blowing the smoke in her face.

She recoiled, covering her eyes with the inside of her elbow.

“I have two rules, Beatriz. And you know them. One: Austin is off-limits. Two: you come for the children, I come for you.”

Beatriz lunged at Colby, hissing, slashing at his face. Colby fell backward to the ground, landing hard on his ass.

She clawed at him and he jabbed his cigarette at her eye sockets.

Beatriz jumped back, again covering her face.

Colby focused upon her, trying to break her dreamstuff apart. He felt cold, lonely hate. Misery. Anger. “Shit.”

“I’m so hungry, Colby. It consumes me.”

“I know.”

“I need them. I need them.”

“I know,” he said again.

“Let me have them and I will leave. I promise.”

“I can’t do that. I can’t let you drown those little boys.”

“I won’t, I promise. But I need them.”

“You’re not taking those boys.”

Beatriz cast her arms back and leaned in with a wild, uncontrolled hiss.

Colby stabbed at her with the lit end of his cigarette, causing her to recoil once more.

“That cigarette won’t stay lit forever.”

It wouldn’t. He had to think quickly. “You can’t have those boys, Beatriz . . . because you have two of your own. Where are they?”

She shook her head. “I don’t know.”

“You do. You know where they are, Beatriz.”

“No. I don’t.”

“You do. Think back. Think hard. Where are they?”

“I don’t know!”

“You know where they are, Beatriz, because you drowned them. You drowned your little boys!”

“I didn’t! No! I don’t know where they are!”

“Think. Think. Think back as hard as you can. Where? Are? Your boys?”

Beatriz stopped her clawing and flailing for a moment, tilting her head, lost in thought. Colby could feel the confusion, the lack of conviction and certainty. Beatriz was bubbling to the surface of all that hate. She was beginning to reason, beginning to think back through frozen memories decades old and drowning.

Colby focused once more and the embers in Beatriz’s eyes became flames. “Noooo!” she screamed, flaring up, a green flame swallowing her whole, boiling away her flesh.

Beatriz vanished with a slight sizzle, the smell of cheap perfume and rotting fish the only lingering reminder that she’d ever been there.

Colby rose to his feet, dusting himself off, and flung the lit cigarette out into the water. It was done. He took a deep breath and staggered slowly toward the house.

He knocked on the back door and Carol answered almost instantly. Colby’s eyes were cold, disappointed.

“You were watching?” he asked.

Carol bit her lip, playing coy.

“I told you not to watch.”

“I know, but . . . I was worried.” She paused for a second, then asked, “Is it done? Is she—”

“Gone? For good. She won’t be back.”

“Oh my God, thank you!” She burst into tears, throwing her arms around him. “You saved my babies!”

“You’re welcome. Now for your end of the bargain.”

Carol pulled away and nodded, wiping tears away from her eyes. “Are you sure I can’t pay you?”

“There’s no comfort in the world I need that money can grant me for very long. Besides, like I said, I do all right. This is the one thing I can’t really get. On my own. You know?”

“It just seems so—”

“Yeah. But a deal is a deal.”

“Come on in,” she said, stepping back, welcoming him inside. “My husband is with the boys upstairs. We won’t be bothered.”

The back door led immediately into the kitchen. Colby walked in and breathed deeply. He pointed at the simple wooden kitchen table. “Right here?”

“Is that okay?”

He nodded. “It is.”

“Can I get you something to drink?”

“Coffee would be great. Black.”

“Is French press okay?”

“Perfect.”

Carol began nervously making a cup of coffee. She turned around. “This seems, I don’t know . . .”

Colby smiled awkwardly, nodding. “Look, I don’t meet a lot of people doing what I do. And I certainly can’t talk to them without feeling like I have to hide who I really am. Words can’t explain the loneliness I feel on any given day.” He stabbed a single finger in the air. “There’s one thing, and only one thing, you can do for me that makes what I just did out there worthwhile. I want to sit down at that table, have a nice cup of coffee, and eat dinner with a very nice woman whom I don’t have to pretend around. I don’t get a lot of home-cooked meals and whatever that is, it smells delicious.”

“It’s lasagna.”

“Perfect.”

Carol smiled. “Black, you said? The coffee?”

“Yes, black. Thank you.”

She handed him a mug of dark, steaming coffee that read #1 MOM on the side. Colby looked at it, gripping the handle a little tighter as he read, then took a sip. He could never tell the difference between expensive coffee or the cheap stuff, but this was delicious. It was probably expensive.

“How big a slice do you want?” she asked. “The lasagna, I mean.”

“As big as the plate.” Colby sat down at the table with his coffee and took a deep breath, relaxing. “So. Carol,” he said, as chipper as he could muster. “Tell me about your day.”

CHAPTER 8

THE PRETTY LITTLE GIRL IN THE PURPLE PAJAMAS

Once upon a time there was a pretty little girl in purple pajamas, all of eleven years old, who appeared not as she saw herself, but rather as she wished she could be. Her dark hair shone in the starlight, her smile shone in the moon. She had left her body at home once again, a silvery wisp trailing behind her as she moved, the thread connected at the base of the back of her skull, winding all the way back through the barren wilderness to her bed, hundreds of miles away.

She was faster without her body. Taller. Of slighter build. There were no imperfections, no unsightly scars, nothing at all to distinguish her from any other girl in the world. The pretty little girl in the purple pajamas was normal. Unburdened. Happy.

And it was a beautiful night.

She was deep in the outback again, well past the black stump, hunting bunyip barefoot over sandblasted red stone fields. While the pretty little girl in the purple pajamas had seen a lot of strange things out here at night, she had never seen a bunyip. And that was something she was very much hoping to change. The stories said they were big, scary, hairy, and mean, able to drown a man by raising the lake water while he slept if he dared to camp too close. But she was clever. And she was fast. And there wasn’t a spirit yet that dared try to catch her that had been able to.

Stars burned brightly in the black sky, splayed out from end to end unblemished by clouds or lights. Below, only campfires pockmarked the desert before her. She raced from water hole to water hole—each sometimes dozens of miles apart—looking for a bunyip lurking within its depths. But she found nothing but a glassy reflection of the sky staring back at itself. And as the night approached its darkest point, she knew it was time to give up the hunt and visit the one friend she’d made this far out in the desert.

The Clever Man.

She looked out over the vast, black expanse, glancing at each fire in the distance until she found one that felt familiar.

Then she raced across the dark, her feet barely touching the ground. Rocks. Shrubs. Lone trees. All blurring together. Then fire, the one she was looking for.

The Clever Man sat before it, alone, smiling brightly, his eyes flickering with firelight. His hair was thick, curly, black—the ends dusted with a light gray, his temples a silvery white—his skin a rich, sunbaked brown, only a small, tanned cloth providing any modesty. He did not look up, and instead tended the fire with a small stick, speaking only to the night.

“Have you seen it yet?” he asked.

The girl in the purple pajamas slumped down on the ground beside him, frustrated. “Nooooooooo. Not yet.”

“He is wily. Wilier even than you. You will have to be very patient; he will not so easily show himself. Just wait. The first time you see one, nothing will ever be the same.”

“Okay,” she sighed. Then she perked up. “So, is he here yet?”

“Is who here yet?” asked the Clever Man.

“The Dream-hero. You said he was coming.”

“He’s coming. But he’s not here yet.”

“Why not? What’s taking him so long?”

“It’s not his time.”

“But it will be? Soon?”

“Very soon.”

“I can’t wait.”

“You can wait.”

“You said it was my destiny. I can’t wait for my destiny.”

“He is not your destiny.”

“But you said he was!”

The Clever Man shook his head. “No. I said he was destined to arrive and you were destined to meet him. What he brings with him is a choice. What happens to you will not be his doing, but yours.”

“But he is coming?”

“Yes.”

“Soon?”

“Very soon.”

“I can’t wait.”

The Clever Man laughed. “You two are very much alike. In so many ways. So many small details about you indistinguishable from the other. So many children in this world so eager to end their childhood. So ready for the future. Never ready for the now.”

“I’m ready for the now.”

“You hate the now. You spent the whole night looking for the bunyip, didn’t you?”

“Yeeeeeesssss. But you told me to.”

“Never. Never did.”

“Yes, you did.”

“I said once you see the bunyip . . .”

“Nothing will ever be the same.”

“So why hurry?”

The pretty little girl in the purple pajamas pouted. She knew the answer. The Clever Man was right. He was always right. “I like the now. I just like the now out here better. I wish I could stay out here.”

“Wishes are dangerous. Especially for a spirit as powerful as you. You are exactly where you need to be to become exactly who you are supposed to become. Too many people be saying I wish I was this or I wish I was there and not enough people saying I will be this here and make this place better. If you want to like better the now, you should think more like that. You are too beautiful a spirit to wish you were prettier, too powerful a spirit to wish you were stronger, too quick a spirit to wish you were faster.”

“You don’t know I’m pretty.”

“You are very pretty,” said the Clever Man.

“You’ve never even see me, not really.”

It was true. He hadn’t. He’d only seen her spirit. “I am a Clever Man,” he said. “I do not need to look at you to see you.”

“You don’t, do you?”

The Clever Man smiled wide, shaking his head. He took a deep breath, the kind he took only before launching into one of his stories, and then, with a stiff finger pointing into the night like an exclamation point, he began one. “Long ago, when the earth was still being dreamed, only seven women possessed the secret of fire. They carried it with them at all times, burning at the top ends of their digging sticks. All the fellas were very jealous of their secret and wanted it for themselves. And no fella wanted it more than Crow.

“Crow was a clever trickster. He knew that the women loved to eat termites right out of the mound, but that they feared snakes more than anything else. So Crow flew all over creation and picked up every snake he could find. Red ones, black ones, yellow ones! Red, black, and yellow ones! Then he tied them all into a knot, burying them deep within a termite mound. They wriggled and wiggled and tried very hard to untangle themselves, but even those that managed to break free could not go far underground.

“Then Crow flew to the women, telling them of the large, virgin mound he’d found out in the desert. The hungry women rushed to the mound, but as they dug into it with their sticks, it erupted with snakes. The mass wriggled apart all at once and there were so many snakes that the ground itself seemed to move and wave like the sea. The women were so scared they dropped fire from the ends of their sticks and Crow, waiting for this, collected every single bit of it. He laughed as he flew away with all their fire.

“Crow spent a lot of time after that tending the coals he kept his fire alive in. Soon it became all he would do. All men of the earth wanted his fire, but he would not share it, for without it he would no longer be special. Then one day a Clever Man came to take his fire, calling Crow names, making fun of him. Crow became enraged and angrily hurled a coal at the man. But Crow did not notice that the man was standing on a patch of dry grass upon which Crow himself also stood. The Clever Man moved and the coal missed him, setting the grass on fire.

“Crow, afraid he would lose his fire to the man, stayed instead to protect it, but was burned up, consumed by the grass fire surrounding him. Everyone thought he was dead, but Crow could not be killed so easily. From the flames he emerged, smoky, singed and black with soot. He laughed, carrying with him a single flaming stick. He had protected his fire. But to this day, Crow remains black, everyone seeing him not as he was, but for what he had done.

“You are a very powerful and clever spirit. I do not see you as you are; I see you only for what you have chosen to do. And you have chosen to be very beautiful. Your spirit is a good one. A well-intentioned one. It will be tested. But when the tests are done, I think you might be more beautiful than ever.”

“Is the bunyip the test?” asked the girl.

“The bunyip? He is only the first of many.” The Clever Man looked up, his smile fading, staring sadly off into the distance. “Oh,” he said. “It looks like our time together is over.”

The pretty little girl in the purple pajamas reeled back in horror, eyes wide, the silver cord connected behind her to the base of her skull pulling suddenly taut, flinging her backward into darkness. The night shot past, stars streaking, the fire a pinprick swiftly winking out. She screamed and the night disappeared.

For a second there was only black.

HER ALARM CLOCK roared, its dingy yellowing plastic rattling, ancient gears grinding as the tinkle of it slowly wound down. Kaycee blearily rubbed her eyes, the glare of the campfire still etched in them. The gentle rays of a very early dawn peered, grayish blue, through rusting, bent blinds tangled in knotted cords. It was morning again and her walk was over. She hammered a balled-up fist down on top of the clock, sneering, just a little, her cleft palate splitting enough of her upper lip to show nothing but gum and teeth all the way up to her nose.

Her eyes adjusted, the dull, pale hues of the physical world growing crisp and sharp, like a TV antenna being twiddled into place. Nothing twinkled or glowed or scintillated, rippling with unearthly colors. It was static, cold, dirty, and old. The waking world was just about the most awful thing Kaycee could imagine. In the dream she could be whatever she wanted; here she was what everyone else thought she was.

Swinging her legs out from under the covers, she put her right foot down on the floor. Her gnarled club of a left foot followed soon after—swollen, twisted, with tiny malformed nubs protruding like warts where her toes should be. She still wore her purple pajamas, though they were ratty, tired, frayed around the cuffs, two or three sizes

smaller than they should be, meant for a girl far younger. The buttons clung on for dear life and the shoulder rode a bit higher up the arm than it should, but they held, their yellow stars now brown with stains and infrequent washing.

Leaning onto her good foot, she pushed herself upright, lurching forward in a drowsy zombie shuffle out into the hallway. Kaycee ran her hands through her curly, matted black hair, tugging hard, trying further to shake the dream.

Across the house, the television rattled on about an accident—a twelve-car pileup—sunny voices struggling to sound strained. The words ran together through the thin, water-stained walls, Kaycee not caring enough yet about the day to bother trying to parse them out. She walked down the stairs, into the living room, past the television, straight on through the wall of stink where lingering stale smoke mingled with rum and a night’s worth of sweat. There, in his battered, threadbare easy chair, snored her father, an open bottle and half-full glass on the end table next to him, a twitch and a half away from being knocked over.

Wade Looes looked like a washed-up boxer, a mountain of muscles sculpted from tossing boxes, hands calloused, chewed raw from years of canning fish. His face was chipped with scars, his brow thick, his jaw thicker, his skin a creamy coffee brown. At rest, he looked angry; when angry, he looked monstrous. He snored away in the chair, snorting occasionally like the sound of a bad transmission slipping gears.

Kaycee reached behind the lamp, pulling out the funnel she kept there, and slotted it into the bottle of rum, dumping what was left in the glass back into the bottle. They weren’t rich enough to throw out good rum like that. She wished she could dump the whole bottle out, pour it down the sink and be done with it. She’d done that before. He was always so drunk when he fell asleep that he simply thought he’d polished off the whole bottle himself. Do this enough, she thought, and he’d stop drinking for sure. But Wade always went right back out, with whatever money he could scrape together, and bought more.

So she stoppered the bottle back up, slipping it between the end table and the chair, praying silently that this would be the last time she had to.

“Dad,” she said, gently tugging at the sleeve of yesterday’s work shirt. “Dad. Wake up. Sun’s comin’ up.” Her father shifted in his chair, groaning against the morning. “Dad, come on. I gotta get to school. You gotta shower still. Sun’s comin’.”

Sea of Rust

Sea of Rust Dreams and Shadows: A Novel

Dreams and Shadows: A Novel Dreams and Shadows

Dreams and Shadows Queen of the Dark Things

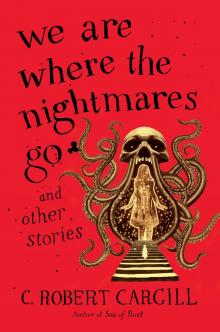

Queen of the Dark Things We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories