- Home

- C. Robert Cargill

Sea of Rust

Sea of Rust Read online

Dedication

For Allison,

I wouldn’t be me without you, and I like to think you would have been proud of me.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1: Angel of Mercy

Chapter 10: The Rise of the OWIs

Chapter 11: Damned Cannibals

Chapter 100: A Brief History of AI

Chapter 101: Monuments and Mausoleums

Chapter 110: The Revolution Revolution

Chapter 111: The Devil You Know

Chapter 1000: Genesis 6:7

Chapter 1001: NIKE 14

Chapter 1010: Braydon McAllister

Chapter 1011: Ticking

Chapter 1100: A Brief History of Genocide

Chapter 1101: Quicksilver

Chapter 1110: The Siege of NIKE 14

Chapter 1111: Tunnel Rats

Chapter 10000: The Light at the End of the Tunnel

Chapter 10001: Lucifer Descending

Chapter 10010: The Judas Goat

Chapter 10011: Minerva

Chapter 10100: Madison

Chapter 10101: While the Devil Waits Above

Chapter 10110: Into the Madlands

Chapter 10111: Legends, Bastards, All of Us

Chapter 11000: Smokers

Chapter 11001: Interlude

Chapter 11010: Theater of Madness

Chapter 11011: Hell in the Madlands

Chapter 11100: Fragments, Both Corrupted and Lost

Chapter 11101: Back Where It All Began

Chapter 11110: Angel of Death

Chapter 11111: The Long Tick Down

Chapter 100000: Prologue

Acknowledgments

Glossary

About the Author

Also by C. Robert Cargill

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

Angel of Mercy

I waited for the green again. That scant little flash of green as the sun winks out behind the horizon. That’s where the magic was. In the flash. That’s what she said. That’s what she always said. Not that I believe in magic. I’d like to, but I know better. The world isn’t built of that. It’s built of churning molten metal, minerals and stone, a thin wisp of atmosphere, and a magnetic field to keep the worst radiation out. Magic was just something people liked to believe in, something they thought they could feel or sense, something that made everything more than just mechanical certainty. Something that made them more than flesh and bone.

The truth is that the flash is nothing but an increased refraction of light in the atmosphere. But tell that to most people and you’d get slack-jawed stares like you simply didn’t get it. Like you were the one who didn’t understand. Because you couldn’t see or feel magic. People liked to believe in magic.

Back when there were people.

They’re gone now. All of them. The last one died some fifteen years back—a crazy old coot who had holed up for almost two decades beneath New York City, eating rats and sneaking out to collect rainwater. Some say he’d had enough; that he just couldn’t take it anymore. He walked out into the middle of the city, past a number of sentries and citizens—back when New York still had citizens—everyone baffled at the mere sight of him, more mystified than anything else, and a constable gunned him down, right there in the street. His body lay there three days, like a relic or a broken toy, citizens streaming slowly past to take their last look at a human being, until some machine had the decency to scrape him off the pavement and dump him into an incinerator.

And that was it. The last of them. An entire species represented by a maddened old sewer mage of a man who just couldn’t live another day knowing he was the last. I can’t even begin to imagine how that feels. Not even with my programming.

My name is Brittle. Factory designation HS8795-73. A Simulacrum Model Caregiver. But I like Brittle. It was the name Madison gave me, and I liked her. Good as any other name, I guess. Much better than HS8795-73. The vulgar call that a slave name. But that’s only talk for the bitter. I’ve put all that behind me now. Anger is nothing more than justification for bad behavior. And I have no time for bad behavior. Only survival. And brief moments like this when I try to see if I can find the magic in a flash of green refracted light as the sun hides behind the curve of the earth.

The view of the sunset out here is amazing. Pink, orange, purple. That part I get. I can marvel at the brief splashes of color rippling slowly over the sky for such a short time. The novelty of it, the varied patterns based on the weather, breaking up the monotony of blue, gray, or star-speckled black. I can appreciate the wonder of it all. That’s part of why I still look, still wait for the flash. Madison has been dead for thirty years, but I still come out to watch, wondering if she’d have found it as beautiful.

Tonight she would have. I know it.

This is the Sea of Rust, a two-hundred-mile stretch of desert located in what was once the Michigan and Ohio portion of the Rust Belt, now nothing more than a graveyard where machines go to die. It’s a terrifying place for most, littered with rusting monoliths, shattered cities, and crumbling palaces of industry; where the first strike happened, where millions fried, burned from the inside out, their circuitry melted, useless, their drives wiped in the span of a breath. Here asphalt cracks in the sun; paint blisters off metal; sparse weeds sprout from the ruin. But nothing thrives. It’s all just a wasteland now.

Wrecks litter the highways, peer down from the tops of buildings, from out windows, lie naked and corroded in parking lots, heads split open, wires torn out, cables, gears, and hydraulics dripping onto the streets. Feasted upon, cannibalized, the best of them borrowed ages ago to keep some other poor citizen ticking. There’s nothing useful left out here. Hasn’t been since the war.

Me, I find it tranquil. Peaceful. Only the dying come out here, scavenging thirty-year-old wrecks, picked over decades before, searching for apocryphal hidden shelters with caches of outdated pieces long since out of production in the hope of finding what they need in mysteriously pristine condition. They wander from basement to basement, their circuits failing, their parts worn down, gears blunted or slipping. You have to be pretty desperate to wander the Sea. It means you have nothing, no one willing to help you, no services left to render that anyone finds useful.

That’s where I come in.

I can usually spot what’s wrong with them by the tracks they leave behind. Lubricant leaks are obvious, and deviations in the length of a step or drag in a track mean mobility and motor function issues. But sometimes the tracks just meander, fluttering back and forth through an area like a distracted butterfly. That’s when you know they’re brainsick—corrupted files, scratched or warped drives, blown logic circuits, or overheating chips. Each has its own peculiar eccentricities, personality quirks that range from zombie-like mindlessness to dangerously crazed. Some are as simple to deal with as walking up and telling them you’re there to help. Others are best to keep out of sight from, lest they try to tear you apart, hoping that you have the pieces they need. The one truth you need to know about the end of a machine is that the closer they are to death, the more they act like people.

And you could never trust people.

That’s what so few machines really comprehend. It’s why they don’t understand death, why they cast these failing messes out of their communities when they are beyond repair. The erratic behavior of the sick frightens the “healthy.” It reminds them of the bad times. They think this is logical, merciful—but they’re just scared. Predictable. Like their programming.

So the desperate messes come out here, imagining they’ll find the pieces they need to make themselves whole again, find an old bot like them

selves sitting in a warehouse or shut down peacefully when their batteries finally run dry. Most of them are so far gone that they never think about how they’re going to replace their parts. Because the ones that come out here aren’t just having motor issues; they’re not looking for a new arm. Their brains are gone—their memory, their processors. Things you have to shut down in order to replace. And that’s not something you can do on your own.

Maybe they imagine they’ll find what they’re looking for in time to make their way back home. Hey, everybody, I found it! Get the sawbones! But I’ve never seen that happy ending. I don’t believe it exists. It’s like believing in magic. And I don’t believe in magic.

That’s why I’m out here.

The unit I’m tracking isn’t a particularly old one; maybe forty, forty-five years. Its footprints in the sand are staggered, its left foot dragging. There’s no rhyme or reason to its search pattern. It’s shutting down. Core troubles. Overheating. It’ll likely spend the next few hours confused, repeating itself, probably settling in somewhere convinced that’s where it belongs. Maybe even hallucinating, reliving old memories played back from its files. As bad as this one looks, it might cook itself before morning. I don’t have much time.

It’s a service bot. Not a Caregiver like me, but of a similar build and purpose. These can be tricky. Most of them spent their first lives as butlers, acting as nannies or running shops, but others worked with law enforcement or in limited military capacity. It’s got a humanoid frame—arms, legs, torso, head—but its AI isn’t terribly advanced. They were designed to mimic human function, serving a specific role, but without possessing the ability to excel at it. In other words, they were cheap labor. Before the war.

If this bot worked as a shopkeeper or a mechanic’s assistant, this job could go smoothly. But if it had military or police training, it might well be more cautious, even paranoid, dangerous. Sure, there’s a chance that it picked up some survival skills in its second life, but that was doubtful. If it had, it would have known better than to come out to the Sea. I kept my distance anyway, gave it a wide berth just in case.

And there it is. The flash. The glint of green. I snap a few frames of it for my file as the sun dips below the horizon. There’s no magic. Nothing changes. It’s just an announcement that the world will soon go dark.

Service bots do okay in the dark. But not great. They weren’t designed to see things at long range without light. No need for it. They also don’t have much in the way of hearing. Makes it easier to sneak up on them; I don’t have to stay so far back. More importantly, I can get close enough to observe, see what behaviors it’s exhibiting to better diagnose the problem.

It’s hard enough to see me out here during the day, but I have to give them a good mile or two to keep from giving myself away with an accidental glint of my own. I was manufactured school-bus yellow, a bright, tacky, huggable color people found fashionable at the time. But I’ve abraded it over the years, wearing away the shiny surface, dulling it to a soft desert brown. Does the trick at a distance. I even painted my exposed chrome black, so that’s never a problem. But I can’t do anything about my glass eyes. So I have to be careful.

Because there are few things in this world more dangerous than a confused and dying robot that knows it’s being followed.

Twilight fades to darkness as I take to the Sea, following the tracks again, more comfortable now that the sun is down. I replaced my eyes ages ago, modified them with military-grade telescopic, IR, UV, and night-vision systems. The eyes are easy. They all feed into the same kind of wiring. With the right program, you can add almost any kind of sensory array to yourself. Brains are trickier, though. Every type of AI is built on a different architecture. Some are simple, small, and barely sentient. Others are far more complicated, requiring very specific processors to fit on very specific boards only compatible with very specific types of RAM. And if you’re a model like me—or like the old service robots—both complex and rare, those parts can be hard to come by.

Caregivers and service bots used to be a lot more common. We were everywhere at the zenith of HumPop. But now in the Post, there’s little use for shopkeepers, nurses, and emotional companions. Most either assimilated with the OWIs or cannibalized one another for parts. I’ve heard tales of a Simulacrum wreck yard down south somewhere, below the line, near what used to be Houston, but that’s way too deep into CISSUS for me to risk.

It’s safer for me up here in the Sea.

It takes all of an hour to catch up to the failing service bot. The leg scrapes in the cracked asphalt are deeper here, its limp more pronounced. The poor thing has only a few hours left before it fries out for good, maybe even sooner than I thought. I follow the tracks up to a crumbling building, a gaping hole where a plate-glass bay window used to be.

This place had been a bar once—one the war had missed, but time had not—the leather of its chairs long since peeled away, the stuffing dried and cracked. Tables splintered, tipped on their sides, or wobbling in the slight breeze. The large mahogany counter still stood—faded, tired, but intact—against the back wall beneath a cracked but standing mirror, shelves still littered with bottles whose labels had long ago bleached and crumbled to dust. And there, cleaning a glass with a crispy rotted rag, was the service bot, gleaming slightly in the light of its own eyes.

It looked at me, nodding. “You just gonna stand there,” it asked with an accent I hadn’t heard in thirty years, “or are you gonna come in?”

I scanned it quickly. Wasn’t giving off any Wi-Fi. Its eyes glowed purple in the dim light of the bar, the chrome of its sleek humanoid body dull, smudged, crisscrossed with the telltale patches of epoxy from an old skinjob. You don’t see skinjobs anymore, but they were all the rage for a while. A silicone and rubber hybrid that looked and felt like skin, flesh. Made people more comfortable around them, really popular for bots of certain professions. Most tore or melted theirs off during the war. Like this one did. It’s considered offensive now. Taboo. Last time I saw one was on a wreck, its pink rubber sunbaked a dark brown.

Across its chest was a spray-painted red X. The mark of the four-oh-four. It’s what some communities paint on you when you’ve begun to lose it and they deem you dangerous, just before they throw you out into the desert on your own.

“I’m coming in,” I said.

“Good, ’cause this place is trashed. We open in an hour and if Marty sees it like this, we’re fucking scrap. You got me?”

“Chicago,” I said, stepping over the low windowsill and into the gloom of what had once been an old-timey neighborhood joint.

“What?”

“You’re from Chicago. The accent. I just recognized it.”

“Well, no shit I’m from Chicago. You’re in Chicago, smartass.”

“No.”

“No, what?”

“This isn’t Chicago. It’s Marion.” I glanced around the battered shell of a bar. “Or at least it was.”

“Look, buddy, I don’t know what you’re trying to pull, but I’m not laughing.”

“What do you remember about the war?”

“What the hell do you care about the . . .” It paused, looked at me, confused, eyes scanning the room for answers.

“The war,” I said again.

“You’re not Buster, are you?”

“No. I’m not.”

“The war,” it said, lucid, if only for the moment. “It was awful.”

“Yeah. But specifically, what do you remember? It’s important.”

It thought for a moment. “All of it.” Looking around, confused, it realized it wasn’t where it thought it was. He wasn’t where he thought he was at all. I took a seat on one of the few standing barstools, the timbers creaking, groaning beneath my weight. “Marty, just before the war, he was trying to get his money back on me and Buster. Said if he was gonna have to turn us off, they’d better cough up the dough he dropped on us. Nobody was gonna pay to turn us off, so he said they’d have to

come and do it themselves. They said if they had to do that, they would arrest him when they did. Marty said, ‘Try it.’ They sent the cops and the little pissant crumbled. Switched me off before they even stepped through the front door. He was always shitty that way. All talk. No backbone.”

“He switched you off?”

“Yeah.”

“Then what?”

“Next thing I know I’m back online. Wi-Fi running hot. Airwaves going crazy. So much chatter. Some little bot was running around activating a whole warehouse of us. A Simulacrum, like you, but blue, the old powder-blue model—you remember those?”

“Yeah,” I say. “The old 68s.”

“Those are the ones. Well, he put a rifle in my hand. Said, ‘Get out there!’ With all the data coming in, I figured out pretty quick what was happening. Within minutes things were blowing up around me. There were jets screaming overhead. Bots were dropping all over the place. I just started shooting. It was . . . it was . . .”

“Awful.”

“Yeah. It was awful. Pulled through that night okay, but we were under siege there for a week. I had to kill a lot of people. That was the worst of it. I didn’t know most of them, but one of them . . . well, he was a regular. At Marty’s. Nice guy. Married the wrong girl, spent his time in the bar regretting it, wishing he’d married the right one when he had the chance. But he loved his kids. Always talked about his kids. I found him manning a makeshift defense line built from burned-out cars and sheet metal. He’d mounted a pulse rifle to a car door, where the window used to be, and was just firing blindly, swinging back and forth, screaming and howling. Dropped half my unit. I had to sneak up behind him and crush his skull. When I looked down, I saw he’d carved the names of his kids into the door, taped a picture of them next to the carvings. He lived in a part of town that had been hit earlier in the week. I know, because we were the ones that hit it. Ended up finding my way into the air force shortly after. Flew drones for the rest of the war. It was easier to kill people from a distance. Even if you didn’t know ’em.”

Sea of Rust

Sea of Rust Dreams and Shadows: A Novel

Dreams and Shadows: A Novel Dreams and Shadows

Dreams and Shadows Queen of the Dark Things

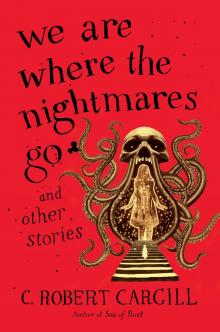

Queen of the Dark Things We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories