- Home

- C. Robert Cargill

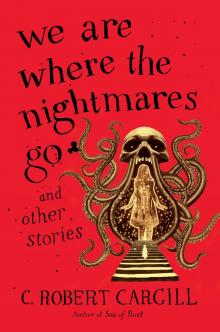

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories Read online

Dedication

For Jessica,

for all the good dreams between the nightmares.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

The Town That Wasn’t Anymore

We Are Where the Nightmares Go

As They Continue to Fall

Hell Creek

Jake and Willy at the End of the World

The Last Job Is Always the Hardest

Hell They Call Him, the Screamers

I Am the Night You Never Speak Of

A Clean White Room

The Soul Thief’s Son

Acknowledgments

Glossary

About the Author

Also by C. Robert Cargill

Copyright

About the Publisher

The Town That Wasn’t Anymore

Wilton Jacobs was a good sheriff. He had to be. Though Pine Hall Bluff was a sleepy, quiet little town, it required a certain amount of finesse to keep straight—a quality Wilton had acquired watching his father, Michael, the previous sheriff, keep the peace. He was an unassuming man, and you wouldn’t think much to look at him outside of his uniform—stout, pasty, a weak hairline eroding his widow’s peak a little each day. But when he put on that star and hat, you could see it in his eyes—a determination, an unflappability. He never lost his temper, never let anyone get the better of him. And if somehow you did manage to elicit a glare from him, he didn’t have to say a goddamned word—his eyes did all the talking. “I’m not moving from this spot,” they said. “You are.”

Pine Hall Bluff was an old mining town nestled high up in the mountains of West Virginia, surrounded on all sides by trees as far as the eye could see, deep in otherwise undeveloped country that had seen its fair share of tragedy and death. The roads were mostly dirt and gravel, with only a handful of paved ones all meant for hauling ore, each winding around through hills peppered with shacks and cheap mid-century company houses. The local mine had been closed for years—not for lack of coal, but for the death of some 227 miners it had claimed in a collapse that broke the back of the town and sunk Coulson Coal, the company that owned it, into bankruptcy. There were few living in Pine Hall Bluff that didn’t have kin down that mine, and fewer still that didn’t lose someone in the subsequent chaos.

But that was all a long time ago. Michael had been sheriff then, and Wilton just a deputy still wet behind the ears. Most people up and left after that—said they couldn’t abide living in a town cursed like it was—but those that stayed carved out what life they could. The town had started with a population of around 3,500. Now there were only a few dozen souls left.

Wilton sat in his truck at the top of Old Miller’s Hill, sucking at the end of a filterless Pall Mall, ashing out the driver-side window, looking down into the valley as the sun crept closer and closer to the edge of the world. Sometimes he daydreamed that the mountains were teeth and one night they might snap shut, the mouth of the world swallowing whole the town, the valley, and all the shit that came with it. But he was never that lucky—the maw of the world gaped wide into the heavens, leaving everything just where it was. Every day the sun rose and the town was still there, a burden his father had left to him; a responsibility he couldn’t bear to abandon. It was a town in name only; a smudge on the map that led to nowhere at all. And he was the law—what little that still meant out here.

With each passing moment the sun sank closer to the horizon, and with it Wilton’s heart into his stomach. He hated sunset. The days in Pine Hall Bluff were quiet, easy, peaceful. It was the nights that were trouble. They were a different kind of quiet. A nervous quiet. A dead quiet. The kind where even the forest shut up lest it disturb the dead.

The truck’s police radio crackled to life, a burst of garbled static like a cough drowning out distant whispers. Wilton picked up the handset, pressed the button. “Go for Jacobs.”

There was no response.

He stared at the radio, waiting to see if there was another burst—turning up the volume a bit to see if there was anything behind the low hiss of the open channel.

“Go for Jacobs.”

Nothing.

Looked like it was going to be a quiet night.

He stabbed out the butt of his cigarette in the ashtray before turning the key in the ignition. It was time to make the rounds. Twilight was only going to last so long.

Father Jeremy Paddock hadn’t always wanted to be a priest. The son of a North Atlantic fisherman, he spent his youth on trawlers drenched in frozen mist, the cold seeping in so deep it made his bones brittle. But when a longline went the wrong way, taking three fingers of his left hand with it, he was saddled with the choice between working belowdecks in the freezer or finding something else to do with his life. He always told people that at the end of the day he was happy he lost half a hand because it was what brought him to God, that he was the very model of the Lord working in mysterious ways, that as he sat alone in the dark of the night in that hospital staring at half a hand, he started to ask God why and God whispered back. He had a calling and it took tragedy to find it.

But now that he’d stood before his maker, stared him in the eye and saw the breadth of his creation, Father Paddock would much rather have had his hand back.

He stood in the back of the church, lighting candles that flickered weakly against the encroaching dark. Originally meant to be a dual-purpose church serving both Catholic and Protestant services, it was an odd building—very mid-century, with sharp corners, aerodynamic flourishes, and a pulley and chain up front that could swap the crucifix for a standard Christ-less cross. But that pulley hadn’t been pulled in years, not since the Lutheran pastor had passed on and, lacking much of a flock anyway, was never replaced. Paddock himself had repeatedly asked for a transfer from his bishop, but every time he did the answer came back: “No, you’re needed there.”

He needed a sabbatical. He needed a new flock. He needed something other than a church in a dead town with a seven-member congregation, only three of whom ever bothered to attend Mass. Like everyone else, he hated Pine Hall Bluff. He just couldn’t leave it.

“Sheriff,” he said without looking up. He shuffled to the side, lighting another row of candles.

“Padre,” said Wilton standing in the doorway, hat in hand.

“You can come in, you know.”

“Doesn’t feel right,” he said. “What with me not being baptized and all.”

“It’s a nondenominational church, Wilt. Coulson Coal built it—not the parish, not God. You know that.”

“Yeah, but you blessed it and all.”

“I can baptize you, you know, if that’ll make a difference.”

“Yeah, but then I’ve got to take all them classes. And you don’t . . . you don’t really hold them anymore.”

“I’ll make an exception,” said the priest, turning around. “You don’t need the classes.”

“I’m not sure God will be all right with me skipping ahead of the line like that.”

“And I’m not sure God cares much about any of that, anyhow. To be honest, I’m beginning to think he doesn’t care about much of anything at all.”

The sheriff nodded, understanding. “Funny how the same bad thing can flip two people like us in completely different directions. Maybe there’s no way to survive something like that without questioning everything.”

“And maybe it’s just this fucking town,” said the priest. “Maybe it just exists to destroy everything it surveys. Maybe it will just hollow us out until we’re nothing, like we were the day everyone went down into that mine an

d never came back up.”

“Maybe,” said Wilton.

“So how are you feeling about tonight?”

“Pretty good. I feel like it’s going to be quiet.”

“You sure?”

“I’m sure it feels that way,” said the sheriff. “Why? You got a bad feeling or something?”

“Not as such. But I don’t have a good feeling about it either.”

Wilton sighed. “I’d sure feel a lot better about tonight if we had a consensus.”

“A consensus has never really been a sure thing.”

“No. I reckon it hasn’t.”

“Would you like to pray about it?”

Wilton looked around the church, still not having taken a step in past the doorway. “No, I’ll say my words in the truck. But, Padre?”

“Yeah?”

“I could really use you believing again. Like, proper believing. You know, just in case.”

“Yeah,” said Father Paddock, “I’ll put in a word with the big man and see what I can do.”

“You do that.”

Jesse Bish wasn’t Irish, but he figured the Irish weren’t as likely to drink in a Polack bar as the Polish were to drink in a Mick one. By the time he figured out that no one in town actually cared, the name Murphy’s had stuck. Not that the bar was particularly Irish. Or particularly anything, for that matter. But it sounded better than Bish’s.

Murphy’s wasn’t so much a bar as it was a gas station that’d had its convenience store gutted and replaced by something that approximated one. There were wobbly lacquer tables scattered about, and the wall behind the bar was nothing more than a series of mismatched glass-fronted mini fridges stuffed full of four different brands of beer—only three of which ever needed to be replenished regularly. Above those ran a shelf holding whiskeys, a handful of vodkas, and a collection of leftover schnapps that no one quite had the stomach to drink. The bar top, though, was finely crafted; hand-built and stained one weekend by a pair of regulars who were tired of drinking at a place less comfortable than their own porches.

The pumps outside still functioned, though they didn’t need to be refueled nearly as often as they used to. The credit card readers didn’t work anymore, but they didn’t need to. Everyone paid by cash these days. Out front between the pumps and the bar was a hand-painted sign reading: gas up while you wait.

People used to find that funny.

There were only two types of people left in Pine Hall Bluff: landowners who were too poor to move elsewhere, and people who felt there was still a job to do in town. Both types drank at Murphy’s.

By the time the sun was setting, Murphy’s was almost as hopping as it got on a weeknight. Will Reilly, an old machinist best known for his thick bushy mustache and his fondness for older whiskeys—only fifteen years or older for Will—sat at the bar with his best friend. Stephen Hill, a mullet-coiffed truck driver who still made his home here, was that best friend. And in the corner sat Rocky Martinez, one of four local rent-a-cops hired to look after the several million dollars’ worth of mining equipment that had been picked up at auction but had yet to be moved elsewhere. Sometimes Murphy’s might see as many as six or even seven people at once. But that was usually Saturdays or sunup after a particularly rough night.

“Wait,” said the ’stache. “I still don’t get it.”

“What’s not to get?” asked the mullet.

The ’stache pointed at his glass. “How the hell is this both whiskey and not whiskey? I’m looking at it. It’s fucking whiskey.”

“Yeah, but for a thing to exist it also has to not exist.”

“That doesn’t make any sense.”

“Sure it does. Look, in order for something to be hot, there must also be cold. In order for something to get wet, there must also be a state we call dry. In order for there to be light, there has to be dark. Everything has an opposite, two states of being—existing and not existing.”

“Right.”

“And in order for there to be whiskey, there also has to be a state of being that it is not whiskey.”

“Yeah,” said the ’stache. “But that’s whiskey.”

“That right there?”

“Yeah.”

The mullet grabbed ’stache’s shot glass and swallowed the contents whole. He slammed the glass on the countertop in victory, asking loudly, “Then what the fuck is that?”

“An empty glass.”

“But is it whiskey?”

“That’s not fucking whiskey!”

“Exactly!” he said, pointing at the ’stache.

“But it still exists. It’s just in your goddamned belly.”

“Being turned into something else,” said the mullet. “It won’t be whiskey for long. It no longer exists. But it did. So was it whiskey?”

“It was.”

“But it won’t be soon?”

“No.”

“So it can be both,” said the mullet. “It just matters at what point in time you’re viewing it.”

“This is seriously the shit you listen to in your truck?” asked the ’stache.

“Sure. Those hauls are long and there’s only so many audiobooks. I mean, once you’ve gotten through all the Koontz and the King, what’s left but the Jean-Paul Sartre?”

“Wasn’t he the one who said God was dead?”

“Naw,” said the rent-a-cop. “That was Nietzsche. He was the German who died of syphilis. Sartre was the Frenchman who turned down the Nobel Prize.”

The bartender, the ’stache, and the mullet all turned to look at the rent-a-cop.

“What?” asked the rent-a-cop. “He’s the only one who can listen to audiobooks?”

The door opened, jangling, interrupting the conversation. The sheriff strode in, hat in hand.

“Sheriff,” said everyone.

“Everyone,” said the sheriff. “He in yet?”

“Nope,” said the bartender. “Not yet.”

“It’s a little late in the day, don’t you think?”

“He didn’t get a lot of sleep last night on account of last week. It’s been pretty rough on him. Can I get you a drink?”

“Soda with lime.”

“How much vodka?”

“I’m on duty.”

“So only one shot, then?”

“Yeah,” said Wilton. “I reckon just the one.” He sat down at the last open stool at the bar. “So what are we talking about tonight?”

Will Reilly chewed on his mustache for a moment before pointing at his empty glass. “How this is supposed to be whiskey.”

The sheriff peered over. “That doesn’t look like whiskey.”

“That’s what I’m saying!”

“We’re talking Sartre,” said the mullet.

“Oh,” said the sheriff. “Then it’s both.”

“Goddamnit!” said the ’stache, banging his head on the counter.

“You know what Sartre said Hell was, right?” asked the sheriff.

“What?” asked the ’stache.

“Other people.”

The bartender paused for a moment, drinking in that thought.

“Maybe that crotchety old Frenchman was right,” said the rent-a-cop.

The door tinkled, opening again. Everyone turned. Jason Manning, the town drunk, staggered in, scratching at a fresh bandage on his arm. He hadn’t showered in days and you could smell yesterday’s alcohol sweating out through his skin. The sheriff sipped his drink and nodded at him.

“You need a seat?” the sheriff asked.

“Nah. I’ll take a table,” said Jason.

“You been drinking?”

“Is that some kind of joke?”

“Do you think I’m joking?”

“I don’t want to assume.”

“Have you been drinking?” asked the sheriff again.

“What do you think?” answered the drunk.

“Could you use another?”

“What kind of question is that?”

“A po

lite one.”

“Then yes. Of course I could use a drink.”

“Set this man up,” said the sheriff.

The bartender looked out the window into the darkening street. “You sure?”

“He deserves it. And I’ve got a good feeling about tonight.”

“A good feeling? Or no bad feelings?”

“I’m optimistic.”

“All right,” said the bartender. “But I’m pouring ’em slow.”

“You do that.” The sheriff swallowed his drink in a single gulp, stood up, and secured his hat squarely on his head. He was all business again. “All right, I’ll be at the station if anybody needs me.”

Wilton sat outside the bar in his truck, smoking a cigarette with the window down, watching the stars slowly poke through the black. Static screamed at him over his police radio—garbled gibberish, angry and disaffected, if even only for a second. He picked up the handset.

“Go for Jacobs.”

Nothing.

“Dad? Is that you?” he asked.

Deputy Milo Manning manned the desk at the silent station house. While he’d never been the brightest or the best of the old guard, he was the only remaining deputy the force had left, making him both now. He meant well, and the fact that he still manned his post, day in, day out, without a real day off, meant the world to Wilton. And Wilton meant the world to Milo.

The phone on his desk was thick, black, and heavy. It was an old phone, ancient really, the kind the phone company used to rent to you before they would let you buy your own—the receiver having enough heft to club a man unconscious. When it rang, it had a deep, wounding clang that tapered off into a chiming whimper at the end. Milo rarely let it get to a second ring. Tonight it was ringing off the hook.

“Sheriff’s station. Deputy Manning.”

The line crackled and popped like a fireplace, an almost imperceptible whisper clawing at the light static of the line.

“Hello?”

No answer. Milo hung up.

Wilton walked in, hung his hat on the limping, three-toed hat rack. “Milo.”

“Sheriff.”

“Any calls?”

“Just the usual this time of night. Awful lot, though.”

Sea of Rust

Sea of Rust Dreams and Shadows: A Novel

Dreams and Shadows: A Novel Dreams and Shadows

Dreams and Shadows Queen of the Dark Things

Queen of the Dark Things We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories