- Home

- C. Robert Cargill

Dreams and Shadows Page 3

Dreams and Shadows Read online

Page 3

“Okay, now I don’t want you home till after five, you hear me? Mommy needs her quiet time alone.” Sylvia picked up the bottle of vodka next to the juice, filling the other half of the glass with it. Colby nodded. “Now you be careful out there. I don’t want you coming home early bleeding from your head, okay? Be safe.”

“I know, Mommy. I’ll be good.”

“You run along now. Mommy needs her shower.”

Colby spun on his heel and took off running for the front door. “Bye, Mommy,” he yelled without looking back. The door opened, slammed behind him, and that was it; he was tearing off toward the woods, making his way fleetly down the street. He passed the large wooden ROAD CLOSED sign that kept cars from turning onto the dirt road, bisecting the woods into two distinctly different patches, and stopped.

Colby looked back at his house just in time to see a car pulling into the driveway. A well-dressed man in a finely tailored suit stepped out, slowly loosening his tie. There was a spring in his step—an urgency in the way that he walked—as if he couldn’t wait for what was behind that door. He knocked, looking both ways as he did. The door opened immediately. Sylvia leaned out, also looked both ways, then pulled him inside by his jacket, the door slamming behind them. Without so much as a thought, Colby turned back to the woods.

There is no place in the universe quite like the mind of an eight-year-old boy. Describing a boy at play to someone who has never been a little boy at play is nigh impossible. One can detail each motion and encounter, but it doesn’t make a lick of sense to anyone but the boy. It’s as if some bored ethereal being is fiddling with the remote control to his imagination, clicking channel after channel without finding anything to capture his interest for very long. One moment he’s aboard a pirate ship, firing cannons at a dragon off the starboard bow before being boarded by Darth Vader and his team of ninja-trained Jedi assassins. And only the boy, Spider-Man, and a trireme full of Vikings will be able to hold them off long enough for Billy the Kid to disarm the bomb that’s going to blow up his school. All while Darth Vader is holding the prettiest girl in class hostage. And just in case things get a bit out of hand, there are do-overs.

It’s kind of like that, only breathless and without spaces between each word. At one hundred miles per hour.

And that was exactly the sort of play Colby was engaged in as he made his way from tree to tree, a stick in hand, fighting off a pack of ravaging elves and wicked old men, led by a one-handed, shape-changing monster. Colby pointed to the sky, commanding a flight of hawkmen to descend upon the elves to buy them enough time for the cavalry to arrive. He swung his sword and cast spells, fighting off all manner of creatures.

Colby spun, a whirling dervish in jeans shorts and a polo shirt, and struck a deathblow to whatever creature was in his head at the time. Instead of whistling through empty air, the stick stopped midstroke, striking with a dull thud across the very real silk-sash-covered belly of a large, ominous figure—one who had not been standing there a moment before. Colby’s eyes shot wide. He was in trouble.

The stranger looked down, his hands resting on his hips, unsure of what to make of the unintentional strike.

He was tall. Not grown-up tall. Abnormally tall. Seven feet of solid muscle upon which rested a jaw carved from concrete, chiseled with scars. His hair, long, black, and as silken as the robes he wore, was pulled back into a ponytail high atop the back of his head. A brightly colored sash looped his waist, a number of ornamental baubles, bells, and buttons completing the garish, almost cartoonish, outfit. The man looked down at the stick still resting on his stomach—which Colby was too frightened to even consider removing—growling softly.

“Hmmmm,” he murmured.

Colby froze in place. “Um . . . uh . . . I’m sorry. I’m real sorry. I . . . uh.”

The man smiled, shifting to good humor in the blink of an eye. “No need to apologize,” he said, bowing. “There was no harm done. In truth, I should be the one apologizing to you. A thousand pardons to you, sir, for I should not have appeared so unexpectedly.” He spoke boldly, with the lofty confidence of an actor on the stage, his voice large and resonant, almost echoing off the neighboring trees without seeming to carry very far at all. He possessed an eloquence to which Colby was unaccustomed, one where even the smallest, simplest words and gestures carried weight.

“I’m sorry,” said Colby, the man’s reply sounding more to him like his mother’s sarcasm than an honest apology.

“No,” boomed the man, shaking his head. “I am the one who is sorry. I am Yashar. What is your wish?”

Colby had no idea what to make of the strange man, but found him intriguing. At first he thought he might be some sort of pirate, but now that he’d said the word wish he was beginning to reevaluate him. “My mommy says I shouldn’t talk to strangers,” he said. “She says that bad men like little boys with red hair and blue eyes, but I told her that my hair wasn’t very red and she said it didn’t matter how red it was, just that it was red. Is that true?”

“There are men that like many things. I am not one of them.”

“You don’t like small redheaded boys?”

The man bellowed a laugh, honestly amused. “No, I am not a man.”

“Well, you’re still a stranger and I can’t talk to you.”

“But I told you my name. I am Yashar.”

Colby crossed his arms. “It doesn’t work that way.”

“Well, how do I become anything but a stranger if you won’t talk to me?” asked Yashar.

“I guess Mommy or Daddy would have to introduce us.”

“What if I told you I wasn’t a man, but a djinn?”

“Like the card game?” asked Colby.

Yashar leaned in close, as if to whisper a carefully guarded secret. “No, like a genie.” He smiled big and broad with all the reassuring boldness he could muster.

Colby eyed him skeptically, folding his arms. “If you’re a genie, where’s your lamp?”

Yashar cocked an eyebrow at Colby, displeased but not altogether surprised. He dropped every last bit of pretense. “Look, kid, if I had a nickel for every time I was asked that—”

“You’d be rich,” Colby said, interrupting. “My daddy says that. Well, if you’re really a genie, prove it. Don’t I get three wishes?”

Yashar turned his head, playing coy for the moment. “Not exactly.”

“I knew you weren’t really a genie.”

“You watch too much television,” said Yashar. “That three wishes and lamp garbage, well, it doesn’t work that way. It never worked that way.”

“Well, how does it work then?” asked Colby with wide, inquisitive eyes.

“Oh, I see: one minute I’m a stranger and you can’t talk to me, but when you find out that you might get something out of it you’re all ears. I don’t know if you’re the right child after all.” Yashar turned as if he was about to walk away. One, two, thr—

“Right child for what?” asked Colby.

“For remembering me.”

“I’ll remember you! Promise!”

Yashar nodded. “Well, we’ll need a little test. Meet me back here at the same time tomorrow. If you remember, you just might be the right child.”

Colby lifted the plastic face on his watch, checking the time. It read 3:45. “What’ll I get?”

“Whatever you want, my boy,” Yashar said with a laugh. “Whatever you want.” He spun around, his robes a kaleidoscopic torrent becoming a colorful smear, before vanishing altogether, his sash fluttering alone on the wind, finally folding into nothing. Where he’d been, he was no longer, and left no trace behind to prove otherwise. But his voice whispered into Colby’s left ear, gently carried by a breeze over his shoulder. “Tell no one. Not a soul.”

Colby stared, dumbstruck, at the empty spot where Yashar once stood. He couldn’t believe it, he could have anything

he wanted. Anything at all. Yashar had said so. This was all so exciting. He turned, forgetting about everything else, and sprinted back home. He ducked, dove and wove about trees, thinking about all the treasures he might ask for. Would he get only one wish? Is that what he meant? Or could he have anything and everything? Oh, he hoped he meant anything. Anything at all. Anything and everything. There was just so much to ask for.

Arriving at the ROAD CLOSED sign, Colby stopped dead in his tracks. The man’s car was still in the driveway. Colby’s watch read 3:47. Crap. He wished that the man would hurry up, finish helping Mommy with her headache and leave so he could go home. But he wouldn’t get his wish until tomorrow, and the more he thought about it, the more he realized that this would be a rather silly and wasted wish. He would wait, no matter how long an eternity that hour and thirteen minutes might be.

He would wait, because when Mommy said five o’clock, she meant it.

CHAPTER FOUR

THE TEN THOUSAND BOTTLES OF THE FISHMONGER’S DAUGHTER

Translated from fragments unearthed midway through the twentieth century, “The Ten Thousand Bottles of the Fishmonger’s Daughter” appears to have, at one time, been collected as one of Scheherazade’s many tales presented in Burton’s The Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night. However, at some point it fell into disuse and doesn’t appear in any complete subsequent copies. Some scholars argue that this is simply a local tale added by an unscrupulous scribe meaning to include his own work in such a respected manuscript, a common practice of the time and one of the problems Gutenberg sought to eradicate with the invention of his printing press. Others argue that it is a lost folktale that became unfashionable, failing to espouse the beliefs of Islam, as many Nights tales do. Perhaps the best argument against its inclusion as a true Nights story is that it does not portray the sultan in a good light, something contrary to Scheherazade’s ultimate goal—that of appeasing her murderous sultan husband. It is included here for the sake of completeness and should not be considered in actuality to belong directly in Nights.

Excerpt from Timm’s Lost Tales: The Arabian Fables by Stephen Timm

Once upon a time there lived a very selfish djinn. While he was one of the most powerful and clever of his kind, he had become infatuated with the lifestyle of man. He would seek out men of this world and grant them wishes, be it great wealth, power, or a multitude of women, and in return he would ask them one simple favor: to make a wish that in no way benefited them directly. These men would often think of wondrous, selfless ideals—feeding the poor, sheltering the homeless, curing the sick. But all the while the djinn had been seeding them with notions that he was in some way trapped or poor or suffering. To each man he told a different tale and often each man—hoping to further gain his favor—would grant the djinn some creature comfort with his spare wish. In this way the djinn amassed such wealth that it began to rival the sultan’s own. This estate afforded him a great many wives, all of whom he loved very much, each spoiled and pleasured in a way no other harem was ever spoiled. This djinn had a good life, one he felt he had earned many times over.

But in this very same kingdom, at this very same time, lived a very selfish sultan. Though the most powerful and respected man of his day, he had grown comfortable with his status and with all of his worldly things. And when he heard about the growing wealth of the djinn, the sultan grew nervous. Soon this djinn’s wealth would eclipse his own and he might one day claim himself to be sultan, ruler of all he surveyed. As far as the sultan was concerned, this djinn was one wish away from stealing everything that was rightfully the sultan’s—all of which was bequeathed to him by Allah upon his birth. And as no djinn was going to take away a birthright gifted by Allah, the sultan summoned together his wisest viziers to hatch a plan to put this djinn squarely in his place.

For days the viziers talked it over and could come to no agreement. Some thought they should put the djinn’s women to the sword and burn his estate. Others, fearing reprisal, thought they should only threaten to put his women to the sword and burn his estate. Still others thought the sultan should absorb the lands and estate as his own, by the will of Allah. But none of these options truly protected the sultan and his kingdom from possible reprisal—for while the sultan’s army was mighty, djinn were numerous and there was no telling how many would come to the aid of one of their own.

It was the sultan’s wisest vizier, a man whose name is no longer known to us, who sat silent for three days and three nights, letting the other men talk themselves hoarse before speaking up. And when he did, there was not a voice left in the room to contradict him. “You waste your time with talk of force and threats,” he said, condemning his fellow advisors. “If you wish to best a man, whether in warfare or in guile, you do not confront his strength. You play upon his weakness.” And with that he laid out his plans to humiliate the djinn and leave him no longer a threat to the sultan. But the vizier demanded a price from the king—albeit a small one—for it is said that a djinn can sense desire in the heart of a man and it was essential to the plan that the vizier be given a reward.

He asked, humbly, for the hand in marriage of the mute virginal daughter of a fishmonger, said to be the most beautiful girl in all the kingdom. The sultan himself had considered adding her as one of his many wives—for what man does not want a silent wife, especially one so beautiful? But this request he granted to his vizier, for the vizier’s cunning was legendary and the sultan wanted never to find himself on the wrong side of it.

The next evening the djinn’s residence was visited by a poor, traveling beggar. The djinn welcomed him in and offered him food. The beggar thanked him and gladly partook of the meal offered him. “You have quite a nice estate,” said the man. The djinn smiled, for he was proud of the home he had created. “It’s not as nice as the sultan’s palace, but it is a fine estate.” The djinn smiled a bit less.

“How is your stew?” the djinn asked of the beggar.

“Oh, fine, sir. Fine. It is an excellent meal. It reminds me of the time I dined with a foreign head of state. He had the most magnificent cooks. They cooked a goat the likes of which you have never tasted, roasted to perfection with the finest of imported herbs.”

The djinn looked at the beggar suspiciously. “How is it that a beggar like you has dined with kings and visited the sultan?”

“Oh, sir. I do not wish to burden you with my tale.”

“Oh, but you must,” insisted the djinn.

“Many summers ago the man sitting humbly before you was vizier to the sultan himself.” The djinn looked upon the man now with great interest. “But the sultan, he is a wicked and most selfish ruler. I served him for many years and asked only one thing of him, the hand of a beautiful girl in a nearby village. But the sultan, once he set eyes upon the girl, decided that he himself must marry her and deprive her of her most cherished innocence. When I dared to speak up, he cast me out—sparing my life for the years of service I had offered him—stripping me of my title and wealth. I have lived upon the kindness of strangers ever since. Oh, if only there was a way to correct these ills!”

Touched by this tale of woe, but even more so enraged by the selfishness of a man higher in station than he, the djinn decided he would help this man. He could sense the longing for the young maiden in the man’s heart and thus revealed his true self to the man. Awestruck by the golden form of the djinn before him, the man fell to his knees as the voice of the djinn boomed through the marble halls. “Sir, this night I will give you the chance to avenge yourself and right these wrongs!”

“Do you swear it?” the beggar asked.

“I do,” swore the djinn. “I will grant you three wishes. The first two are for you. The third must benefit someone other than yourself. Do you promise to do this?”

“Oh yes. Yes I do.”

“Then what is your first wish?”

“I wish for the sultan to grant me the hand of the wo

man I desire most.”

The djinn nodded his head, clapped his hands, and made it so.

“What is your second wish?”

“That no matter what, you do not in any way harm the sultan or his viziers for what they have done, nor may you rob them of anything rightfully theirs without their knowledge.”

“Why not?” asked the djinn, puzzled by this request.

“Because if I let harm come to these men, it would make me no better a man than they.”

The djinn smiled and nodded approvingly. Truly this was a man of character. He nodded his head, clapped his hands twice, and made it so. “And your third wish?”

“That all of your possessions, your estate, and your wives be immediately bequeathed to the sultan.”

The djinn was immediately shamed. He had been tricked. In a rage, he drew back his arm to strike the man but could not, for this was a vizier of the sultan’s and he could not harm him for what he had done; the djinn knew that now. It was only then that he truly understood what he had done.

“You swore an oath, djinn. Grant me my third wish.”

A tear came to the eye of the djinn. His estate, all of his possessions, and the wives he had loved so much; in a moment, they would all belong to the sultan. Sadly he nodded his head, clapped three times, and made it so.

“Now, I order you out of the sultan’s estate, djinn.” The vizier smiled, ordered the servants to tend to the residence in his absence, and returned to the sultan to claim his bride.

Shamefully the djinn walked out of the sultan’s estate and for three days and three nights continued without stopping, trying to get as far away from his old life as possible. When he could walk no more, he found a nice inviting branch in a large fig tree and fell into a deep sleep.

The next morning a young farmer was collecting figs from his trees when he accidentally stumbled upon the djinn. Startled by the disturbance, the djinn awoke angrily, lost his balance, and fell from the tree. The man dropped immediately to his knees and begged the djinn’s forgiveness. It was then that the djinn looked around and, seeing himself surrounded by fields of fig trees, realized he had mistaken the farmer’s orchard for simple woodland. He begged the farmer’s forgiveness, but the farmer would not hear of it.

Sea of Rust

Sea of Rust Dreams and Shadows: A Novel

Dreams and Shadows: A Novel Dreams and Shadows

Dreams and Shadows Queen of the Dark Things

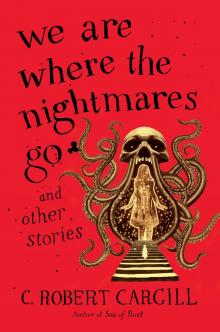

Queen of the Dark Things We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories