- Home

- C. Robert Cargill

Queen of the Dark Things Page 16

Queen of the Dark Things Read online

Page 16

“Stop saying their names!”

Austin looked quizzically across the bar at Yashar. “Is there something I missed?”

Yashar nodded. “He thinks if he doesn’t say their names—”

“That’s not what I think,” said Colby. “I just don’t need to draw any more attention to myself.”

“If they’re watching you, Colby,” said Austin, “then they’re watching you. You can’t hide. Not here anyway.”

“I wasn’t, I mean . . .” Colby paused and took a big sip of whiskey. “I’m not trying to choke the magic out. I just wanted to . . .”

“Wanted to what?”

“To . . . protect children.”

“I know,” she said. “And that’s why I like you.”

“You like me?”

“Sure,” she said playfully, the twinkle returning to her eye. “I get it. You want to feel like you’ve done something. Like you’ve left something behind. You’re not alone. You’re idealistic. Like a politician.” She looked at him sternly. “Except that you weren’t elected.”

“Neither were you.”

“Touché.” She smiled. That thought hadn’t dawned on her. “Well, I mean I was, but I wasn’t.” She thought some more, trying to find the right words. “I just want what’s best for everyone, but I don’t know the future. I see what’s happening here. I see what you’re getting into. And I’m worried about you.”

“There’s nothing to worry about.”

Austin looked at him longingly, her pretenses dropped, face awash in worry. “Please,” she said. “Don’t get involved in this.”

Colby leaned back on his stool, confused. “I don’t understand.”

“Whatever they’re asking you to do, don’t do it.”

“I don’t know what they’re asking me to do. All I know is that she’s coming.”

“The girl?”

“The girl.”

“Whatever they need you to go do with her, you can’t go. I need you here.”

Colby grew cold. “Need me for what?”

“Don’t make me say it.”

“Need me for what?”

“I just—” She stammered a little, trying to keep cool. “I need you here.”

“Need. Me. For—”

Austin stroked the top of Colby’s hand with her fingertips, setting his arm ablaze with tingles, then folded her fingers into his. She stroked his hair back over his ear with her free hand, running a single finger down along it to the lobe. “Don’t. Do. This,” she whispered. Then she batted her eyelashes ever so slightly, almost imperceptibly, her eyes large and pleading. “Please.”

Colby squeezed her hand tight, his chest caving in on itself. “I don’t even know what they want me to do.”

“Austin,” said Yashar, paternally. “Please don’t mess with Colby like that.”

She slipped her hand away from Colby’s. “Would you rather I do this the other way?”

“Which way would that be?”

She scowled, spoke with bass in her voice. “The fire and brimstone don’t-make-me-kick-your-ass-and-rain-a-world-of-shit-down-on-you way.”

Yashar put both hands up. “Okay, the first way was fine.”

Colby shook his head. “I didn’t do anything. Why are you doing this?”

“Someone died today, Colby. A demon took one of my people.”

“You act as if that doesn’t happen every day in this city, in one way or another.”

“Not for show,” she said, bitterly. “Never for show! That demon killed someone just to fuck with you. And I’ll be damned if I’m going to let him get what he came for.”

“Is that what this is about? Making a point?”

Austin teared up, just a little, the slight glisten making her eyes bluer, glassier, more like the open sea. “His name was Ernesto. He had two kids, Julian and Selena. He met his wife bagging groceries when they were seventeen. She was a cashier. The first day they worked the same line together was like . . . well, you could have powered the whole building with the sparks those two were giving off. He loved his wife and kids as much as anyone I’ve ever known and he never hurt anyone.

“I had a beer with him once. He sat there the whole time nervous that I was going to hit on him. Nervous. Most guys, especially the married ones, they have a beer with a girl, they hope she flirts. Even if they haven’t the faintest inclination to cheat. Makes ’em feel good. Like they’re still a man. Not Ernesto. He was terrified of his wife thinking he might be flirting with another girl. Didn’t want her to think for a second that he might find another woman in the world to be as pretty as her. Because he didn’t. So we talked about the Spurs and about his kids and then his kids some more.” She giggled, her eyes smiling for a second as she thought back, before darkening all at once atop a sneer. “So fuck Asmodeus. And I don’t care if he hears me.” She looked up at the ceiling. “You hear me, asshole? Asmodeus! Come on down here and look me in the eyes, you little bitch!”

“Whoa, whoa, whoa!” yelled Yashar, waving his hands. “There’s no need for that.”

“Oh sure,” said Colby. “Now you’re not cool with invoking them by name.”

“He won’t come,” she said, before yelling at the ceiling again. “He’s a FUCKING PUSSY!”

“Jesus,” said Colby. “You are still drunk from last night.”

“I lied about that,” she said, taking another sip of her beer. “I started drinking again this morning.”

Austin stood up, slammed the rest of her beer, then tossed the bottle to Yashar, pointing at him. Yashar caught it single-handedly, a little pissed at the disrespect, but not wanting to offend his guest.

“Make sure he doesn’t get any deeper in this,” she said, before turning to Colby. “Let them sort out their mess themselves.” Then she walked out of the bar, muttering to herself about goddamned demons.

CHAPTER 28

THE ORPHAN STORY

The Clever Man, the pretty little girl in the purple pajamas, and the boy Colby sat around the fire, Mandu once again blowing his didgeridoo. The night was alive, the fire crackling with hints of stories, the flames momentary spirits that whispered secrets before fluttering away toward the stars. The pretty little girl huddled closer to the fire than the others, her arms crossed, rubbing her hands up and down, trying to warm herself through her pajamas, shivering slightly.

Mandu looked over the fire at the two. “Once, very long ago,” he began, “there was an orphan boy whose mother and father had both died in terrible ways. The mother had been careless, wandering too close to the water’s edge during the rainy season, while not paying enough attention to the crocs swimming in the river. The father had been loud and boisterous and picked one too many fights with other fellas. Neither died particularly well. So it was very sad for the boy, who now lived with his grandmother.

“The grandmother took good care of him. Fed him, taught him, treated him in all ways like a son. But the other children of the camp were cruel to him. Having no one to teach him how to hunt or properly throw a spear, he fell out of favor with them, and they taunted him for being an orphan. One day he went to his grandmother, saying, ‘Grandmother, they won’t play with me or share their food.’ His grandmother asked, ‘Who won’t?’ To which he replied, ‘The other children.’

“Grandmother understood. She handed him a snack of honey and cakes and said, ‘Don’t you concern yourself with them. They are greedy, terrible children, and one day their bellies will ache with hunger and they will know of their cruelty.’ But the boy wasn’t comforted. He refused to eat and only cried louder.

“His crying grew so loud that it awoke the Rainbow Serpent from his dreaming. He uncoiled himself from under the earth and followed the crying to the village. He burrowed his way under and into the hut where the orphan was crying and swallowed both him and his grandmother whole. The serpent was so large that as he emerged, the hut lodged on its head like a hat. Hungry from his long slumber, he began eating villagers, swallowing fami

lies one by one.

“The people ran, terrified by the Rainbow Serpent trying to end the world. Soon the village was completely empty, but the Rainbow Serpent, he was still hungry. So he moved along the earth, his body weighed down by all the people in his belly, carving a groove in it. Finally, he came upon another village and set about eating it as well.

“By this time, he had swallowed so many warriors, all of whom poked the serpent from the inside with their spears, that he looked like he was covered in a thousand thorns. As he ate, he grew slower and slower, and finally a few warriors were able to climb upon his head and deliver the deathblow, killing the Rainbow Serpent for good and for all. Then they cut open its belly and set free all the people.”

“What happened next?” asked Colby.

“Nothing,” said Mandu. “That’s the end of the story.”

“I don’t get it.”

“Neither do I,” said the girl.

“The Rainbow Serpent helped dream the world into existence. He was one of the most powerful creatures in history. But he was woken from his sleep by the tiniest, most insignificant of people. And he was killed by mere men who possessed nothing more than spears and bravery. Normal men. Great and terrible things can come about because of a single person wanting nothing more than attention. And the end of the world can be stopped by men brave enough to try. No one is too big or too small to change the world, for better or for worse. That’s the lesson.”

“Oh,” said Colby. “I get it now.”

“I hope so,” said Mandu. “That story will mean more to you than most.” Mandu put the didgeridoo back to his lips, playing again, letting Colby meditate for a moment on his words.

“Can I ask you something, boy?” said the pretty little girl in the purple pajamas, still trying to warm herself.

“My name is Colby.”

“I don’t care what your name is.”

“I do. And I don’t like being called boy. What’s your deal with names?”

“My deal?”

“Yeah, your deal. What is it?”

“Names don’t mean anything out here. Who we were doesn’t mean anything out here. All that matters out here is who we are. Out here I am who I want to be, not what anyone tells me I have to be.”

“Everything out here has a name, you know,” said Colby.

The pretty little girl in the purple pajamas gave him a dirty look, her face pinched and puckered as if to say, I know that. “I don’t have a name out here yet.”

“Why not?”

“No one has given me one.”

“I’ll give you one.”

She shook her head. “No. It doesn’t work that way. You have to earn it.”

“What’s your question?”

“What?”

Colby leaned forward. “Your question. The one you wanted to ask me.”

“What are you doing out here? I mean, you clearly aren’t, you know . . . indigenous.”

“Indigiwhat?”

“Aboriginal.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You’re not a black.”

“Oh! No. I’m not.”

“But you can see me.”

“Yeah.”

“How? And why are you on walkabout?”

“Oh,” said Colby, thinking for a second about how best to explain it.

“You ever hear of a djinn?”

“No.”

“How ’bout a genie?”

She nodded, smiling queerly. “You mean like from a lamp? Like on TV?”

“Yes. But never, ever, ever say that to one. Because they hate that.”

“They? You mean they’re real?”

“Why wouldn’t they be? Little girls who fly around in their dreams are real. And bunyips are real.”

“Yeah, but genies? That just sounds . . . silly.”

“They’re called djinn. And I made a wish with one. Well, two actually.”

“So you haven’t gotten your third?”

“It doesn’t work that way. You know, you’d think it would, but . . .”

“What did you wish for?”

“To see the things other people couldn’t. Fairies, bunyips . . .” He motioned to her. “Dreamwalkers.”

“Why?”

“Because I didn’t like it at home and I thought that this would be better.”

“Is it?” she asked.

“Sometimes. No one ever tries to kill me at home. But there’s no one around there I really like either.”

“You like people out here?” She motioned to the desert around her.

Colby nodded. “Oh yeah! Mandu is great. Yashar—he’s my djinn—he’s awesome. I’ve got this friend Ewan who is a fairy boy. I’ve met angels and mermen and all sorts of things. You.”

“Me? You don’t know me.”

“Not real well. But I can tell you’re cool. I like you already.”

She shuffled around awkwardly. “Why? Because you think I’m pretty or something?”

Colby looked away bashfully, his cheeks reddening. “Nooooo. That’s not it.”

Mandu smiled secretly behind his didgeridoo.

“You don’t think I’m pretty? I’m pretty and I’m tall and I’m fast. You don’t like that?”

“I like you because you’re . . . you know . . . the way you jumped on the bunyip and you weren’t afraid of it.”

“Why would I be afraid of it?” she asked.

“I was afraid of it.”

“Oh, well . . . you think I’m cool?”

“Yeah.”

“And it’s not because you think I’m pretty or something.”

“No.”

She smiled, tucking her hair behind her ear and dragging the back of her hand under her chin. “Thank you.”

“So will you tell me your name already?”

Her smile evaporated and she frowned, pushing him away playfully. “No,” she said in all seriousness. Then she looked up at the stars, the sky so black this far out that there were literally thousands of them swimming together in a deep sea of night. “You know, the Clever Man told me once that in the Skyworld, each star was a campfire of the dead. That they come together with their dreaming or tribe and at night we can peer across the gulf of time and see their fires winking back at us.”

Colby seemed incredulous. “Campfires?” He looked at Mandu, who only nodded, still playing his one, droning note.

“Campfires on the other side of the sky,” she said, mired in the romance of it, her teeth chattering lightly. “I like the idea. You know that where we go when we die is a place like this. Around a fire. With friends. Telling stories. Where everyone gets to be exactly who they dream they were meant to be.”

“I like that,” said Colby. “That place sounds nice.”

“Why is it so cold out here?” she asked, her body almost convulsing with shivers.

Mandu stopped playing. The night grew quiet except for the crackling of the fire. “Oh,” he said sadly. “Our time is again too short.”

The pretty little girl in the purple pajamas looked over at him, terrified, the cord attached to the back of her head growing suddenly taut, yanking her backward. She vanished into the dark.

Colby looked at Mandu, his eyes wide, confused. “Where did she—”

“Home,” said Mandu. “She’ll be back. She always is.”

“Who is she?”

“I told you. She’s a dreamwalker.”

“No, I mean, what’s her name?”

Mandu smiled, shaking his head. “You know, I never thought to ask.”

CHAPTER 29

BESIDE HERSELF

Light. Blinding. Almost green. Then it goes out, fading. Tracers trickling across the eyes, fireworks soaring through space. Then light again. A whine, high-pitched ringing in the ears. Everything too bright to make out. Shapes in the light, not a one of them clear, crisp. The whine again, then light. The sound of a truck hitting a wall.

“Clear!” shouts a voice.

Th

en a circle of light. Bright. Blinding. Tracers across the eyes. Then nothing.

The pretty little girl in the purple pajamas stood in back near the wall of a severe white room, doctors and nurses surrounding a cold steel table on which lay her tiny, blood-soaked body. Beside them, a large box beeped—beep beep beep—with a display tracking her heartbeat, a bag of blood in the hands of a nurse fed through a tube into her arm.

“She’s back,” said one of the nurses while another put away a set of defibrillator paddles.

The girl watched the doctors fiddle with her limp body, flipping it over, trying to sew together the back of her head. She looked so small. Tiny. She’d never seen herself like this. She’d stood outside her body, looking down on it as it slept, but never while other people were around. The adults didn’t look like giants, they looked normal. She was the one who looked delicate, slight, a kitten in the mouth of its mother.

It was the first time in her life she realized just how young she was.

She walked over to the table, stood by the doctors, bathed in the glow of the fluorescent light at the end of a robot’s arm affixed to the ceiling. The pretty little girl was warmer now. Her shakes were subsiding, and she felt cool instead of cold, warmer every minute.

She couldn’t be sure how long she stood there watching, time was different out here, outside of her body, her perceptions warped, bent by the dream. But when she was relatively certain she was okay, and they had put most of the eggshell mess of her skull back together around her silver cord, she knew it was time to go. So she soared to the back of the room, passing through the doors as if they weren’t there, out into a long, glaring hallway, the lights dazzling, a white so bright she had never quite seen its shade.

The hallway seemed impossibly long, as if it went on forever. She floated, passing a nurses’ station blaring with sounds, flashing lights, then on to the waiting area. That’s when she saw him. Over to the side, sobbing into his hands—her father, Wade. Next to him sat a doctor with a serious face.

“ . . . coma,” the doctor said, the only word she’d arrived in time to make out.

Wade cried openly, almost wailing as he talked, his speech still slurred with drink. “It’s my fault,” he said. “I should have been there. For her. If I hadn’t been, you know, I mean, I could have heard her. Could have gotten her here sooner.”

Sea of Rust

Sea of Rust Dreams and Shadows: A Novel

Dreams and Shadows: A Novel Dreams and Shadows

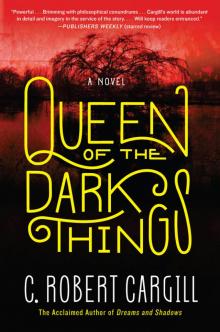

Dreams and Shadows Queen of the Dark Things

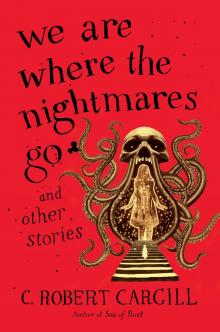

Queen of the Dark Things We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories

We Are Where the Nightmares Go and Other Stories